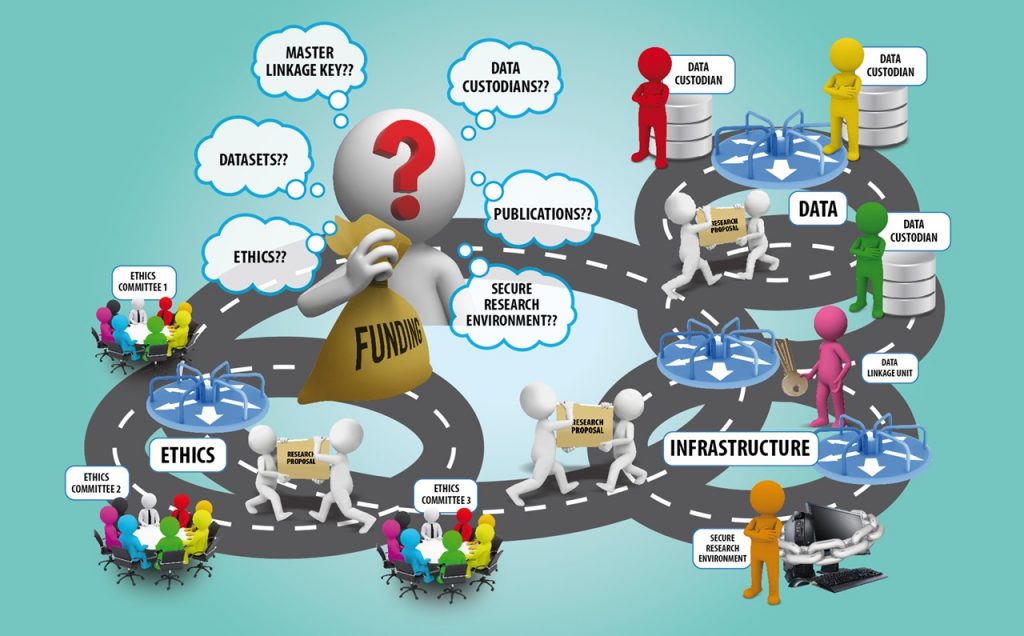

One would think that the process of obtaining data to conduct health and medical research in Australia would be straightforward. Unfortunately, it’s not. Researchers are constantly plagued by incessant delays and lengthy negotiations – all which stem from the fact that they have to go through a variety of different processes before their projects can commence.

The processes for obtaining datasets are incredibly unwieldy. They’re riddled with inefficiencies and duplication, which means researchers are pitted into an unwilling dance between multiple sets of data agencies, custodians, data linkage key and infrastructure providers, all whilst they’re chasing approvals from multiple ethics committees. The end result? The pace of Australian health and medical research (HMR) is slowed, drastically.

The story of Dr Jones below is a case study using an example researcher. It is based on the experiences of a few different researchers we have spoken with. Through it, we’ll examine some of these problems. While you’re reading, bear in mind that it’s only a small glimpse into the myriad of frustrations involved in attempting to get access to the data required to conduct Health and Medical Research.

For a detailed review of the processes, documentation and applications required to conduct national data linkage in Australia, please read this paper published by PHRN.

Running around in Circles

Calling Dr Jones

Dr Cameron Jones is a senior health economist and a data scientist at Oz University. Dr Jones is passionate about the possibilities that data analytics offer for improving health and healthcare services. He’s decided to pursue a project that is aimed at reducing the time it takes for patients in remote areas to access emergency services.

To do this, he needs to link data from four different datasets for analysis. He’s also got two additional researchers on board – Margaret and Gagandeep. It’s safe to say they’re all very excited to proceed. Surely they’ll have no problem accessing the data they require to improve the quality of care for those living in remote areas?

As a first step, Dr Jones prepares a research protocol. It identifies the problem he and the team want to address, the types of data they wish to use, and their research analysis method.

Data Access

Having secured funding, Dr Jones and his team begin discussions with data agencies that hold the data they need. Each agency has specific individuals who are ‘data custodians’. These custodians grant permissions to access their specific datasets. Taking the time to make access requests to each custodian is a lengthy process.

In order to link the different datasets they now have to speak to a different entity – the data linkage unit, who is responsible for providing the keys to linking data. The team then find out that they may not use their own research environment to store and access linked data, but will have to approach another agency – the secure infrastructure provider who has been specified by the data linkage unit. Yet again, this agency has a different set of requirements to be completed.

The data custodians, linkage key and infrastructure providers all have their own application processes. They all check if Dr Jones’ project has obtained ethics clearances and other approvals before they can provide any data or data-related information.

Satisfying all these requirements leads to much wasted time because of information duplication.

Dr Jones wishes he could simply make his request to a single national data entity which could then liaise with the different agencies for him: the process would be much simpler.

Ethics clearances

To get their ethics clearances, Dr Jones and his team have to apply with the national health research ethics committee, and the Oz University ethics board. Because the data cover different states, Dr. Jones needs to go to the ethics committee of all states, and also since the research tries to answer questions about Aboriginal health, they need to apply for ethics clearances from the Aboriginal health ethics committee too.

However, each committee wants information about the data before they can provide any sort of clearance.

This leads Dr Jones and his team to a paradox. On the one hand, they can’t get ethics clearances until they can provide data-related information to the committees. At the same time, they can’t get this information without the required ethics approvals. Unsurprisingly, this leads to what seems like an endless back and forth between the committees and custodians.

After several months, Dr Jones is able to convince the custodians to provide their metadata to the ethics committees. The project can finally move on.

Consent

However, one ethics committee requires that consent be individually obtained from each of the participants who has provided data to the datasets that Dr Jones and his team want to access. Things are delayed further. Hard copies of consent forms have to be mailed to individuals – many of whom have changed addresses, or died. Dr Jones and his team then launch into the mammoth follow-up task of retrieving the completed consent forms.

Many months later…

Dr Jones, Margaret and Gagandeep have spent considerable time and energy and have talked to at least twelve different agencies and committees without doing any research on the project. However, they’ve finally overcome their many obstacles and frustrations and are ready to begin.

Unfortunately, due to changed personal circumstances, Margaret is unable to continue any research work. Dr Jones identifies a new team member, Deborah, as a replacement. Now they have to recontact each ethics committee and custodian to give Deborah data access, resulting in more delays and information duplication.